Talk Business and Politics reports:

A mental health summit held Wednesday (May 25) in Fort Smith covered treatment and incarceration issues with which resolution likely requiring new laws and new thinking at the state level.

Leon Evans, who spoke to legislators and other state and Sebastian County officials at the summit, dealt with such issues as he worked to implement the Bexar County (San Antonio) Jail Diversion Program in 2003.

"If the only tool you have is a hammer, then every problem starts to look like a nail.”

That was the thinking Evans said he had to overcome to find solutions. Evans knew a large part of the Texas jail’s overcrowding problem stemmed from mistakenly incarcerated individuals suffering from mental health issues. But to change that dynamic, he would have to first convince police officers how they’d previously been trained to handle crisis situations needed retooling.

He would also need to convince law enforcement, courts, mental health providers, hospitals, and legislators to work together in addressing the problem head-on.

THE WORST PRISONERS

Evans shared his experiences on Wednesday (May 25) at the Fort Smith Convention Center as the featured presenter for the Sebastian County Mental Health Summit.

“It’s just not right to have someone go to jail for an illness, and that’s what we did in Texas,” Evans said describing his motivation for the program. After doing some research, he found “30 to 40%” of inmates had mental health issues, and “they don’t make good prisoners.”

“They’re hallucinating, potentially suicidal, and stay three to four times longer than a violent offender who’s arrested because they don’t have money to get bailed out,” Evans explained. “A lot of times a judge won’t let them back in the court unless they’re lucid, and a jail is a terrible place to be lucid. Some also require a medical unit or some kind of special observation, so they cost three or four times more than what the general population costs. It adds up.”

Beyond the financials, Evans said, there is a “human issue” behind it, and with only 25% to 30% of those arrested ever getting convicted of a crime, “they’re going to get released and won’t get hooked up in treatment, so that means they’re going to re-compensate and be back over and over and over.”

Therefore, the drive of the program became about diversion – recognizing mental health issues as early as possible to keep individuals suffering from said issues out of jail and with the immediate and/or long-term care they needed to escape the cycle and lead independent lives.

Police officers would be on the frontline of this charge, but getting them up to speed wasn’t easy.

‘COPS, NOT SOCIAL WORKERS’

A frequent complaint Evans heard in the early days of implementing his Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) training program was “we’re cops, not social workers.” But to deescalate crisis situations involving individuals with mental health issues, police officers would need to become a bit of both, “talking down” subjects before diverting them to a program better equipped to meet their mental health needs.

If implemented correctly, the CIT would steer individuals in danger of being locked up out of crisis situations and direct them to mental health professionals better suited to provide diagnosis, care, and treatment.

Thirteen years have passed since, and the implementation appears to be working out. According to Evans, Tthe Bexar County Jail Diversion Program has saved taxpayers over $50 million; diverted more than 17,000 people from jails and emergency rooms; trained over 2,600 law enforcements officers in the 40-hour CIT Training model; trained approximately 250 school district police and administrators in the Children’s Crisis Intervention Training for Schools; and reduced overcrowding for the jail from overcapacity to 500 empty beds.

A ‘RIGHT-NOW THING’

Evans’ program has won numerous awards and been utilized as a template for other police departments throughout the world. Sebastian County hopes to follow Bexar’s lead and bring similar reforms to Arkansas.

According to Sebastian County Judge David Hudson, the time to do so is now.

“It’s a right-now thing,” Hudson said following Evans’ presentation. “We can translate best practices in Texas into the reality of Arkansas, but the key to doing so is to get multiple parties engaged. I don’t know what all of the answers are going to be, but I know it has to come from the community.”

Hudson said it would have to include state, county and local community resources coming together as well as the general public’s understanding of the issues.

“We have to continue to educate the public on what the issues are so they can support responsible action,” Hudson said. “Data is important. We’ll need reporting of jail inmate data as well as those we can divert to treatment or counseling. Knowing the recidivism rate, knowing which inmates in the jail are getting psychotropic medication, (and) how many events occur involving the mentally ill with law enforcement.”

Hudson also said it would be necessary to take stock of “what we have here with service providers” in order to establish collaboration between each entity. Furthermore, there would be the challenge of “identifying funding streams.”

Sebastian County Prosecutor Dan Shue spoke to that at Wednesday night’s summit, stating that in terms of support fees, the Sebastian County task force has looked at having both defendants and taxpayers foot the bill for cost of implementation. Shue also called on state legislators to enact “enabling legislation” in order to set the stage.

“Terms are going to have to be defined,” Shue said to an audience that included State Reps. Justin Boyd, R-Fort Smith, Charlotte Douglas, R-Alma, Mat Pitsch, R-Fort Smith, along with State Sen. Terry Rice, R-Waldron. “If you look back, there are perhaps a half a dozen different statutes dealing with drug courts, both pre-adjudication and post-adjudication drug courts, and some of those have been on the books since 2003; but there is a complete lack of enabling legislation on this issue. There is Supreme Court Administrative Order No. 14, which you could drive a Mack Truck through. It’s very broad, and that’s not what we want. We want some anchoring based on law. That’s what lawyers and judges do. They need that guidance, and having all three branches of government in agreement — the legislature, the governor, and the judiciary – if we have that kind of consensus, it will make this much more successful.”

SEBASTIAN COUNTY OVERCROWDING

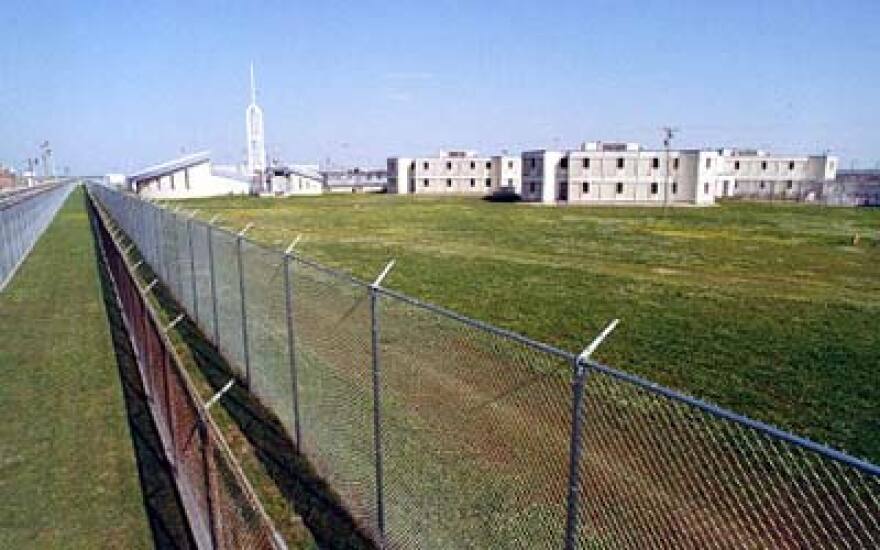

For Sebastian County Sheriff Bill Hollenbeck, reform can’t come soon enough. His jail’s “actual bed population” is 352 while the “managing population,” or the maximum target number of inmates to have at once, is 320.

“As of today, we are at 475, so that’s not good at all,” he said, adding that of that number, “we’re probably treating at least 60 to 70 prisoners for mental illness, and these are the ones that we’ve just been able to identify. The ones that we haven’t identified are the ones that get arrested and get bonded out, within four hours to four days, and they haven’t been able to act out an issue; so that number is much higher than the people we actually treat.”

When asked about how urgently reforms would be needed, Hollenbeck said, “We’re there.”

“We either get serious traction on this, or we’re going to have to build on, and that’s the last thing that I want to have to do,” Hollenbeck said, referencing the potential tax increase as the reason he hopes to avoid it. “The last time we added on was about 10 years ago and before that the jail was built. We’re at that 10-year mark where it’s time to either be smarter with our money or reduce this recidivism rate with these same individuals over and over and over again.”

Hollenbeck also said that how much traction a potential Sebastian County Jail Diversion Program gets could be a factor in having to pay other jails to house some of the county’s overcapacity.

“Quite frankly,” he said, “Crawford County is building that new jail, and at some point, I’m going to have to have a conversation with the Sheriff over there about it.”